In the fifteenth century, various expeditions were launched from European soils to gather information on the coasts of Africa as well as discover new trading routes to the Indies. Not only would new routes be added to the existing maps of sea-voyagers from this Age of Discovery, but eventually entire continents would be added to what was previously assumed to be the ends of the world.

The physical map of the world may have been finalized long ago, but from a microbiological perspective there are still countless fascinating and almost mind-boggling niches that remain undiscovered and unstudied. A plethora of microbial communities have been discovered in the most unlikely of places, like naturally occurring acid hot springs, drainage from acid mines, radioactive sites and radioactive waste, salt lakes, and many more. Up until this point of history, we have lacked the means necessary to fill in many of these blank spaces on the microbial map. Modern advances in technology are just now making further investigation into the far reaches of our world and the different microbial species possible, including further discovery of hydrothermal ocean vents.

Early Deep-Sea Vent Exploration and Limitations

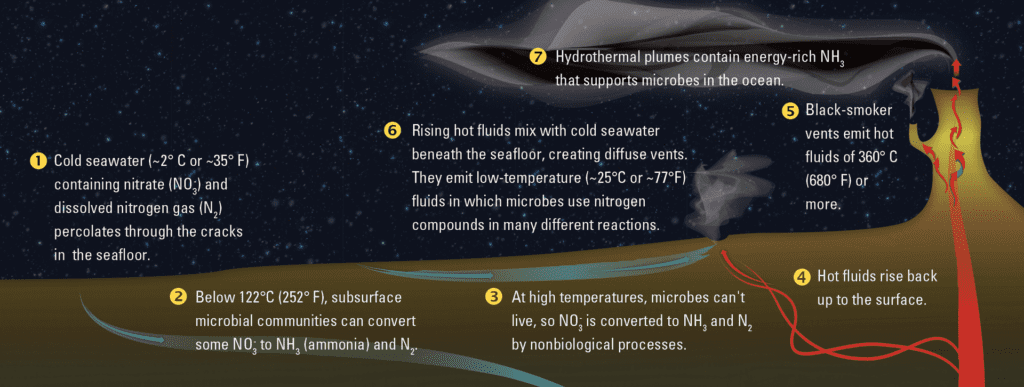

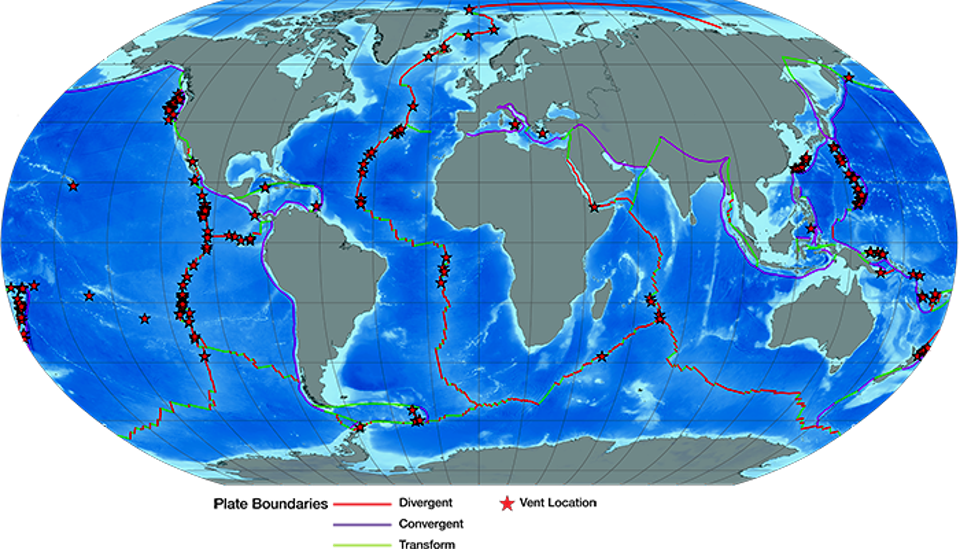

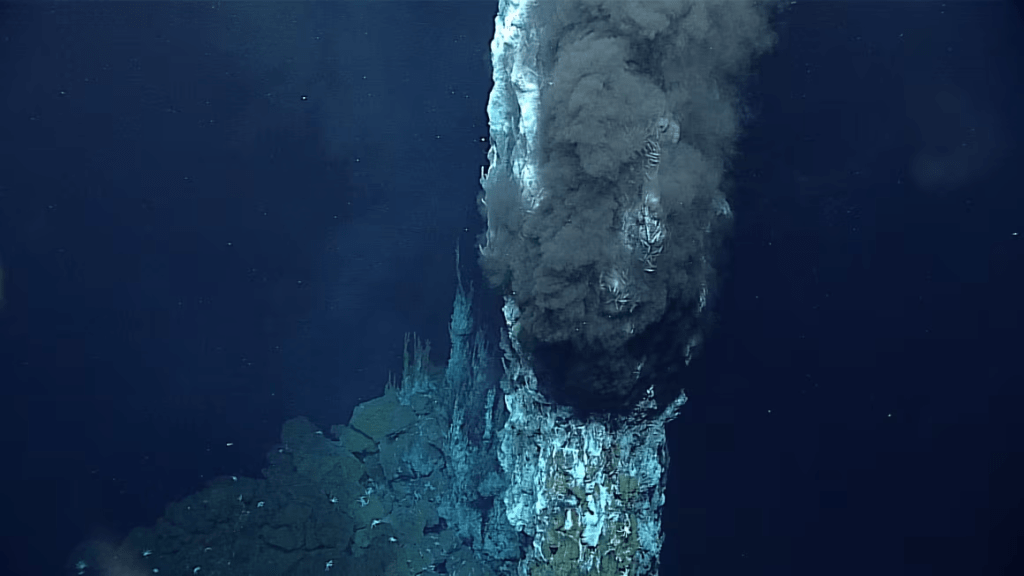

Deep sea vents, or hydrothermal vents, occur at the points where Earth’s tectonic plates are gradually pulling apart from each other. The fissures from these separations allows for water to seep below to magma that wells up as a result of the plate separation. The interaction of the magma with the frigid waters at the ocean’s floor results in a series of unique chemical reactions that remove oxygen from the environment and cause the water to become acidic. The heated water that passed through cracks rises back to the floor surface at extreme temperatures – 400ºC (750ºF) or greater – but the immense atmospheric pressure prevents the water from boiling. Even more chemical reactions and precipitations occur once this super-heated water interacts with the icy, oxygenated waters outside the vent, producing an extreme but unique environment.

Life at 4,000 meters or more below the surface of the water is harsh – the pressure is immense, the water is bitterly cold and the lack of sunlight leaves the ocean floor in utter darkness. The conditions become even more drastic at hydrothermal vents as the waters fluctuate drastically from frigid to scorching temperatures and the chemical composition of the surrounding area is acidic and potentially sulfuric depending upon the thermal deposits. The combination of these factors makes analysis of any life at these sites very difficult. Initial in-depth analysis of deep sea vents did not begin until 1977, when the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute’s (WHOI) sent the Woods Hole’s R/V Knorr Deep Ocean Submersible Alvin, usually referred to simply as Alvin, on the Galápagos Hydrothermal Expedition off the Panama Canal.

What the initial investigators aboard the R/V Knorr Alvin were expecting to find is anyone’s guess. Given the myriad of conditions present at these hydrothermal vents and lack of resources traditionally required by most lifeforms, what could possible eek out an existence in such a place?

The answer: quite a lot, actually.

A Whole New World: Discovery Deep Vent Micro-Diversity

Microbes capable of surviving in excessively harsh environments such as those posed by hydrothermal vents – conditions like excessive heat, cold, salinity, alkalinity, acidity, or radiation – are referred to as extremophiles. The majority of extremophiles found at hydrothermal vents are thermophiles and hyperthermophiles. While many extremophiles are archaea, several other forms of microbial life can be found in extreme settings. Since 1977, a number of different species of archaea, bacteria, protists such as algae and fungi, and other single-celled and some multi-celled predatory eukaryotes have been identified at a number of hydrothermal vents. As there is no sunlight and areas surrounding hydrothermal vents lack the traditional nutrients many microbes found in less extreme environments rely upon, hydrothermal microbes have adapted to utilize different forms of energy. Rather than being photosynthetic in nature, hydrothermal vent species have created a complex, interwoven microbiome whose survival is based upon the by-products of chemolithotrophic organisms, heterotrophic, or mixotrophic microbes that can use methane, sulfur, and various metal byproducts of hydrothermal vent activity to generate energy, that are integral to the microbiological food web of hydrothermal vents. Each of these extremophiles is capable of producing unique intracellular machinery specifically adapted over time to withstand the adverse environment, factors that can be studied and used to revolutionize scientific research, industrial production, pharmaceuticals, and countless other aspects of everyday life. While each hydrothermal vent hosts a unique compilation of microbials based upon water temperature, water pH, atmospheric pressure and water depth, a large majority of the extremophiles present at hydrothermal vents are classified as thermophiles or hyperthermophiles.

Current Progress and Future Implications

Already, numerous advancements in science and technology have been made from the knowledge we have gained studying how extremophiles have adapted to their environments over time. Heat stable enzymes from thermophiles like ones found in hydrothermal vents provide more efficient, more effective processes for everything from food preparation to pharmaceuticals. These innovations are just the beginning. Emerging research suggests that factors from thermophiles and hyperthermophiles could play major roles in future biomedical treatments regarding immune response in inflammatory conditions, cancer, gene therapy, and viral diagnostics. Models from known thermostable enzymes have also been utilized to further understand how these microbes construct thermostability. This knowledge combined with the ability to artificially construct proteins could be pivotal in how pharmaceutical companies choose to synthesize novel heat-stable medications and vaccines in the future.

Conclusions

Hydrothermal vents are home to a wide variety of microbes, and our knowledge of these fascinating microcosms and the potential they may hold will only continue to increase. Recent upgrades being made to Alvins will allow for even greater quality of exploration on expeditions of hydrothermal vents. These remodels along with the discovery of new hydrothermal vents and new species within vents previously charted that may hold unknown microbial species rich with biotechnical potential indicate that there is still plenty more for marine and microbiologists alike to map in the deep oceans below.

Leave a comment