Everything within the modern world, it seems, requires some form of energy. Appliances require voltages of varying degrees from outlets. Houses need warming and ventilation. Coffee needs brewing. Lightbulbs need lighting. Generators in hospitals and industrial plants need generating. Phones and computers and all the other countless technological gadgets to be owned need recharging. Cars require fuel, or if they are exceptionally modern, an electrical boost. No matter which way you turn, it’s energy, energy, energy.

Current Power Sources

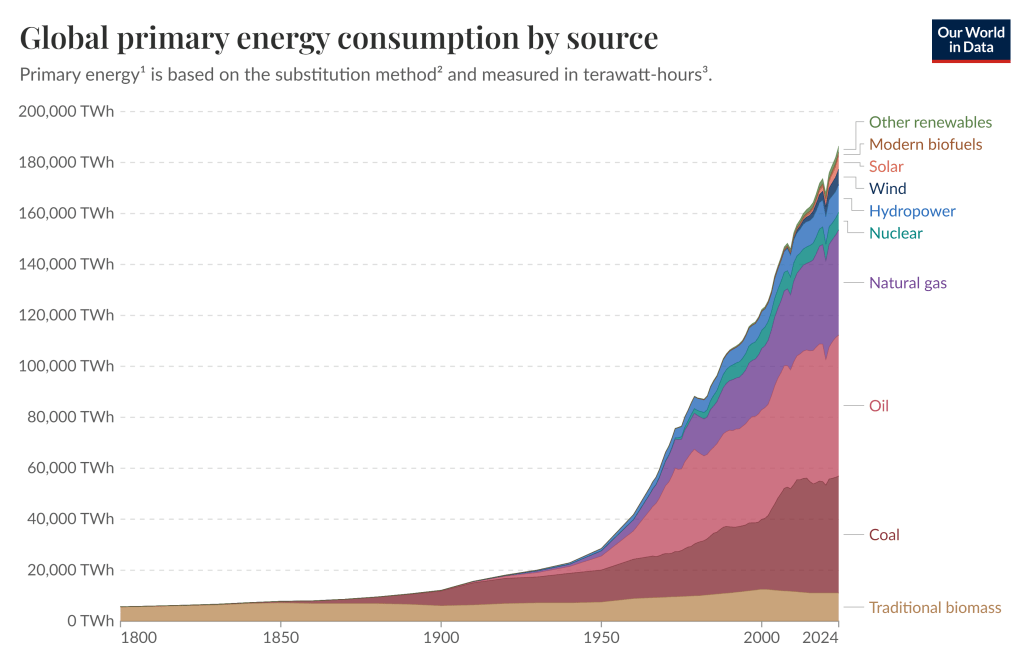

We use a lot of power. In 2024, it was estimated that globally, the primary energy consumption was 186, 383 TWh. Simply put, one TWh, or one Terawatt-hour, is the equivalent of one trillion, yes one TRILLION watts of energy used within the of span one hour. If you start to do the math, that is a lot of energy-efficient 10 watt LED light bulbs per person.

As a society, we’ve come up with quite a few ways to generate the massive amounts of energy we require to keep us going from day to day. Fissures, both natural and man-made, give us access to water at varying temperatures and pressures below the Earth’s surface that can generate both heat and electricity. Solar panels can capture and convert the radioactive waves of the Sun into electricity. Likewise, turbines in wind farms convert the kinetic energy generated from the wind pushing blades in a circular motion into electricity. Nuclear reactors split atoms to release bursts of usable energy. Lastly, there are the ever-dependable coal, oil, and natural gases that can be utilized to generate electricity, heat, and energy.

Problems with Current Energy Sources

Having a variety of energy choices available is optimal, since not all energy choices are equal. Also, some options, as we have discovered, that have short-term benefits may have long-term or even permanent repercussions. Wind farms are generally located in scarcely populated areas and rely on a source that is unpredictable – weather. Solar panel production has become more affordable, but similar to wind turbines, the energy derived is dependent upon the weather. Nuclear reactors generate toxic waste that is difficult to safely dispose of, and malfunctions within reactors have historically had devastating consequences. The prolonged burning of coal and fossil fuels has led to an increase of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, elevating global temperatures and consequently setting off a chain-reaction of abnormal weather patterns and global anomalies.

But our seemingly endless demand for energy doesn’t stop simply because there are some bumps in the road. As technology, machinery, and artificial intelligence become more and more integrated with our everyday lives, our need for energy will likely increase beyond that which we already consume. Furthermore, our need for energy isn’t the only thing that is growing. We, as a global population, are increasing alongside our growing need for novel sustainable energy resources, so much so that the world population is estimated to grow to 9.8 billion people by 2050. So what resources can be found everywhere around the globe that we could tap into in order to help with this energy problem?

Funnily enough, some of these resources look remarkably similar to the things that can grown in your fish tank.

What’s even more interesting is that if you put these microscopic critters together, you not only have the potential to generate energy but may also have the potential to undo some of the damage done to the environment by previous energy sources.

Methanotrophs

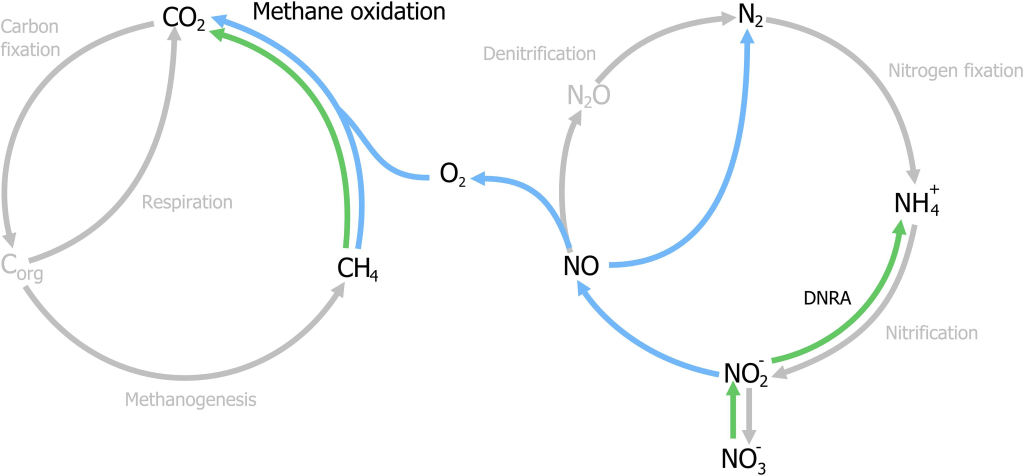

While the greenhouse gas that gets the most attention is carbon dioxide, the second leading cause of climate change is methane. Methane is lighter than oxygen, highly flammable, and in nature is created from the decomposition of vegetation in swamps or wetlands. Methane can also be found in volcanos, oceanic vents, within deposits along continental margins, and in the Arctic permafrost. This natural resource occurs readily in nature and is necessary in order to maintain a climate suitable for life. Too much methane in combination with other greenhouse gases however, and the climate will become overheated. Fortunately, just as we need oxygen to breathe and plants require carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, there are bacteria in the world that utilize methane for metabolic processes.

Methanotrophs are bacteria and archaea that are capable of oxidizing methane through a process called methanotrophy and turning the greenhouse gas into carbon dioxide as well as several other by-products. This is possible under certain conditions due to particulate and soluble methane monooxygenases (pMMO’s and sMMO’s). Two different classifications of methanotrophs exist -aerobes and anaerobes. The end result is the same in that methane is transformed into carbon dioxide. The main difference is that aerobic, or oxygen-dependent methanotrophs, rely solely upon oxygen to perform this chemical reaction, whereas anaerobic methanotrophs initially use nitrogen based compounds to eventually oxidize methane. Many different species of methanotrophs have been found in a variety of biomes, from deep rock ground water to hot springs to salt lakes.

Algae

Algae are microbial masters of variety, as they come in all shapes, colors, and sizes. Some, like diatoms, measure in the micrometers, others, like green algae, can vary in size and color depending on the species and various cellular components present, and giant brown kelp of Macrocystis pyrifera have been known to grow blades 3 feet long. Algae belong to the Protista kingdom, which predominantly consists of unicellular eukaryotic organisms, and most algae are marine-based, lack a true root-system, and are capable of photosynthesis. Algae contribute greatly to many aquatic food webs and are also staples in human food, health, and cosmetic industries. Lastly, algae are of great environmental interest due to their capabilities of capturing and removing excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Enterobacteriaceae

The Enterobacteriaceae genus consists of gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria that can be found in a number of locations. Most bacteria within this species are motile, are not spore-forming, and are able to utilize glucose and lactose to generate energy. Bacteria within this genus are also classified as facultative anaerobes, which means that they are able to generate energy from sugars in the presence or absence of oxygen. Given their tendency to be potential beneficial or pathogenic in nature, many bacterial species within this group, such as Salmonella enterica, Shigella sonnei, and Escherichia coli are well known and extensively studied.

The Sum of All the Parts…

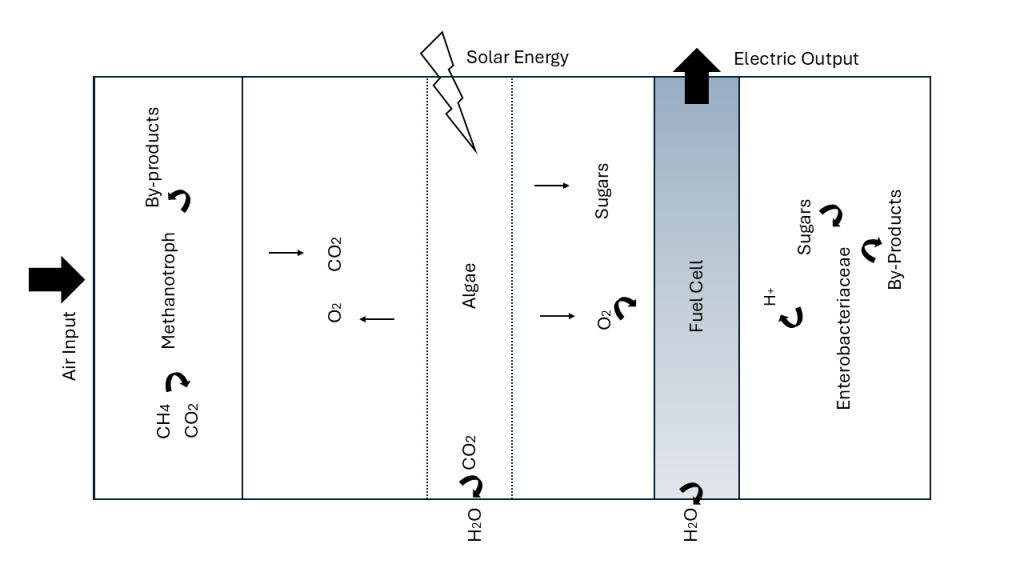

Using microbes to generate energy is hardly a novel concept. Many people have done this before, from creating biofuel to generating electricity to creating batteries from wastewater. But options, as previously discussed, are necessary in the energy industry, and new technologies are developed from ideas that had to start from somewhere. So bear with me as I present my own take on yet another symbiotic microbial platform that simultaneously utilizes two of the prominent greenhouse gases in our atmosphere.

The input carbon dioxide and methane would be separated and vented to their respective locations. For this proposed model, the methanotroph of choice would be Methylococcus capsulatus, as it is well studied, it is capable of growth in media, and it is an obligate aerobe that would utilize the oxygen from the algae to produce carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide generated from the M. capsulatus and the initial carbon dioxide from the air input would be fed to the algae of choice, which is Chlorella vulgaris. C. vulgaris is a microalgae that is efficient at carbon dioxide capture, is capable of generating multiple sugars that can be utilized by various Enterobacteriaceae, and can generate biomass that can be repurposed for other forms of renewable forms of energy such as biofuel. C. vulgaris, through photosynthesis and utilization of both sources of carbon dioxide, would generate oxygen necessary for both the oxidation of the methane by the M. capsulatus and for chemical reactions of the fuel cell to generate the electrical energy. The Enterobacteriaceae for this platform would be Enterobacter aerogenes, as this bacterium is capable of utilizing sugars produced by C. vulgaris and has a high hydrogen conversion rate under anaerobic conditions. The hydrogen generated from the E. aerogenes would be fed into the fuel cell to interact with the oxygen from the C. vulgaris to generate electricity, as well as by-products of heat and water.

Conclusions

This is, obviously, a first draft of a generalized symbiotic platform with hypothetical suggestions of microbes that could potentially work. Would some mechanical and structural issues have to be resolved? Without a doubt. Would some of the conditions, like the temperature, pH, media content, or air percentages of all of the microbes, need to be adjusted individually to find optimal levels for growth and production? Absolutely. Would some of the by-products of the microbes, such as the succinic acid from the fermentation process of E. aerogenes, need to be addressed? Invariably. But in the end, that’s what the development of innovative technology really is – tinkering with an idea until it actually works. Symbiotic microbial models currently in use and such as this offer us opportunities to begin generating power from self-sustaining, self-rejuvenating, environmentally friendly sources to move society closer to a cleaner but no less energetic future.

Leave a comment